A Quiet War

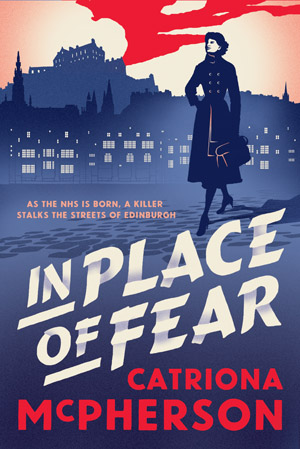

In Place of Fear is Helen Crowther’s story. It’s about her trepidatious leap into professional life from her tenement background, about the fears of her parents, about the scorn (or is it envy?) of her wee sister, and about the judgement of neighbours and strangers alike about a girl like Helen getting above herself. Indeed, an early working title was The Upstart.

But it’s also about her marriage to her childhood sweetheart, Sandy, and the pain and puzzlement she feels about why things have gone so terribly wrong. I didn’t mean to write the relationship that way; it came naturally out of me giving Sandy a war record I know of from my own family.

My maternal Grandfather, James “Mac” MacDonald, was captured in Germany in early 1940 and spent the next close to six years in Stalag 383, as a prisoner of war. He came home changed: quiet overall; utterly silent on the subject of the POW camp; and haunted for the rest of his life by what we now know as PTSD.

The only vague reference I ever remember him making to those years was when one of my sisters said “I’m starving!”, just as a dinner was being dished up. ‘Naw, hen. You’re not starving,” he said, very quietly. Otherwise, we saw the effects of the camp in two ways: his carpe diem attitude and his ability to eat absolutely anything. If he came home late (from the pub or the bookies, or both) and his dinner was dried out and stuck to the plate, he would chip it off and devour it. Sometimes he’d entertain his granddaughters, by putting pepper on his pudding or jam in his tea. We giggled and marveled, watching the Mighty Mac Who Could Eat Anything.

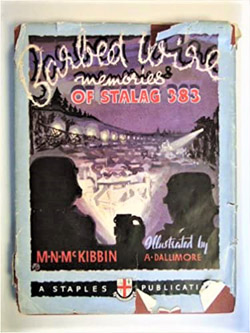

It was years after he died that I found out what underlay these bits of fun and that one quiet remark. It was the merest chance that I did too. It just so happened, you see, that another soldier from Stalag 383 wrote a memoir, Barbed Wire.

In the book, McKibbin describes a sustained act of quiet heroism. The prisoners had two options. They could work in the camp, making supplies for the German military, and be rewarded with three hot meals a day or they could refuse to comply and be kept in a state of near starvation on what were called “non-compliance rations”. This is what they decided to do. They lay on their bunks conserving energy and were given some bread and some potatoes every day. Each man took a turn to divide the rations around the hut, and then each man made the decision about whether to eat his own slice of bread and cooked potato all at once to have a break from hunger, or portion them out through the day, never feeling full but never feeling quite so empty.

They did this for almost six years. A very quiet war.

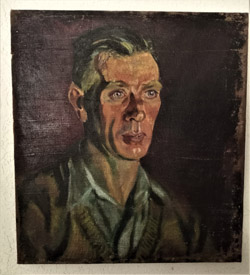

The only relief came in the form of occasional Red Cross parcels containing tinned food, clothes, hobby supplies and tobacco. It was thanks to a Red Cross donation of paints that I have a record of my grandad in the stalag. One of his fellow prisoners was an artist – Terry Frost, later one of the Newlyn school of colourists and eventually a member of the Royal Academy, knighted for his contribution to art. Frost struck a deal with his camp-mates. If they gave him one half of their sackcloth pillow cover for him to paint on, he would do their portrait on the other half. Mac was one of the prisoners who sacrificed his pillowcase to gain a portrait. What is more, unlike many of the other men, he brought his portrait home and kept it. I have it now – properly stabilised and remounted by a conservator – hanging in my bedroom.

It is beautiful – Terry Frost was a skilled painter – but it is hauntingly sad too. It somewhat contradicts the message sent along with the notice of capture in 1940. This is a short document explaining in printed German that Mac was now imprisoned, when he had arrived, the address of the camp, and the authority under which he was held. At the bottom though was a hand-written sentence, in curly script, that said “He is well”. That was a kindness extended by . . . presumably some conscripted soldier working in Stalag 383 whose humanity was intact. It served to reassure my granny that Mac wasn’t wounded or physically ill. But, looking at the portrait and remembering my grandad when he came home again, I’m not sure it was true.

In the book, I’ve let Helen not understand Sandy. I’ve allowed her to be angry and bewildered by the changes in him but, even as I wrote this troubled relationship from her point of view, Mac, Grandad, RSM James MacDonald of the Royal Scots Fusiliers, was always there with me.

The jacket description of A Place of Fear:

| Edinburgh, 1948. Helen Crowther leaves a crowded tenement home for her very own office in a doctor’s surgery. Upstart, ungrateful, out of your depth – the words of disapproval come at her from everywhere but she’s determined to take her chance and play her part. |

She’s barely begun when she stumbles over a murder and learns that, in this most respectable of cities, no one will fight for justice at the risk of scandal. As Helen resolves to find a killer, she’s propelled into a darker world than she knew existed, hardscrabble as her own can be. Disapproval is the least of her worries now.

Catriona McPherson (she/her) writes preposterous 1930s detective stories about an aristocratic sleuth, darker (not difficult) contemporary psychological thrillers, and comedies set in the Last Ditch Motel in fictional (yeah, sure) California, She has just introduced a fresh character in June’s 1948-set IN PLACE OF FEAR, which finally marries her love of historicals with her own working-class roots.

Catriona is a proud lifetime member and former national president of Sisters in Crime. www.catrionamcpherson.com