Once upon a time, they lived happily ever after

When I conceived of the story in my new book, I worried that no one would know it was a fairytale deep down, that no one would get it. Part of the problem stemmed from setting it in the post-industrial landscape of Scotland’s central belt; another bit was caused by my protagonists being a van driver, an accountant, a grant-writer and a retail entrepreneur – no woodcutters here.

But then I hit on the idea of naming it A GINGERBREAD HOUSE. That’s all it took.

As the book opens, Ivy, Martine and Laura decide separately to swallow their misgivings and visit the delightful little cottage where they’ve each been invited. Early readers – the book came out in the UK last month – report ripping through these chapters muttering “Don’t do it. Text someone. Drive away.” I think the title is responsible for 98% of that, and maybe the last 2% is the echo of other things I’ve written. There’s nothing in the beginning of the story itself to cause goosebumps.

What did fairytales do to us, I found myself wondering.

One thing they did was stick. When I asked friends in an informal online poll: “If I say ‘fairytale, what’s the first one that comes to mind?” no one was lost for an answer. Thirty-six different fairytales were mentioned as the most burned into people’s psyches.

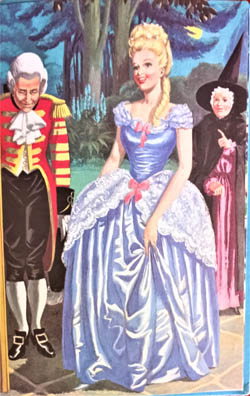

And the top answers? Cinderella got 21 votes, Hansel and Gretel 17, and Little Red Riding Hood 15. So that’s a wolf eating Grandma, ugly sisters sawing off their heels to make the shoe fit, and those kids poking gnawed-clean chicken bones through the bars to convince a cannibalistic witch that they weren’t ready for the pot yet. Only Goldilocks – a comparatively benign tale of child neglect and potential bear attack – came close, with 9 votes. The gentler fairytales – The Princess and the Pea, The Elves and the Shoemaker, Sleeping Beauty – came in at 4, 3, and 2 votes. It’s as though a substandard mattress, an internship and a long nap just don’t have the same effect on the emerging consciousness of impressionable children.

That’s one reason I feel confident in concluding that these votes didn’t arise in happy memories of cosy bedtimes. The comments, too, made it clear that some the of the legacy was mild trauma, or even not-so-mild trauma. Finally, I believe it’s leftover fear at play for everyone because it is for me.

Of course, as a 21st century feminist, I should find “some day my prince will come” the most horrific fairytale trope of all. When it’s Cathy Earnshaw, Jane Eyre and the second Mrs de Winter, I do want to shout at them to learn what a bad boyfriend looks like and move on. But in fairytale form the romance and posh frocks still get me.

Neither are the fairytales that disturbed me most as a child, and can still unsettle me now, the ones we could call “spectacularly bad decisions” – Snow White, Jack and the Beanstalk, Rapunzel. (Pro tip: don’t swap your baby for a salad.) Even when I was tiny I reckoned anyone who did fall for the cow/bean deal had it coming. And I wouldn’t have touched the apple.

The “massive over-reaction” fairytales weren’t the ones I had to put outside my bedroom door so I could sleep either. People signing up for 100 year deals like the first days of phone plans, more parents giving their kids away, goblins losing it over a bit of a beard trim and beasts losing it over someone picking their roses? You’re supposed to dead-head roses; it prolongs the flowering.

No, the one that still makes me shudder is Rumpelstiltskin. Now, it has got a spectacularly bad decision in it (it’s our old friend, the promise to give away a baby), and it’s got a massive over-reaction in it (the wee guy asks a question and, when he gets a straight answer, he kicks a hole in the floor, falls in and is gone forever), but what scared me was the way the story rolled inexorably on, for no reason. I didn’t mind scary stories that made sense, but this one makes none. Why did the miller say his daughter could spin straw into gold? Why didn’t the daughter tell the king her dad was talking mince? Why did the king need all that gold anyway? What was he playing at, if he didn’t? Why did Rumpelstiltskin rate a necklace and a ring if he could spin straw into gold? Why would you marry someone who locked you up and made you spin all night? How could you forget that you’d promised to give your baby away, when your only distraction was . . . you just had a baby? Why would you jump around your front garden singing a song about your name, when you had a baby-sized bet hanging on keeping it secret.

To me, Rumpelstiltskin was random and inexplicable. It broke the contract between story and reader. And that made it more frightening than any fairytale has a right to be. There’s a reason no one’s ever put Kafka’s The Trial out in wipe-clean, pop-up format.

So let me assure everyone that, when I’m writing instead of reading, everything in the story eventually makes sense. If you decide to come to along to A GINGERBREAD HOUSE, you might be puzzled for a while but you’ll understand it in the end. And no one marries a total psychopath, just because he’s royal. Not this time.

Cx

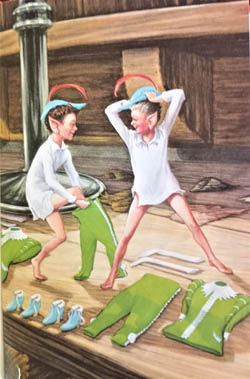

A note on the pictures: Ladybird was a Penguin imprint, putting out 56-page board books, inexpensive but lavishly illustrated – as you see – and with a delicious powdery finish to the paper. They were in their heyday in the sixties and British people my age are likely at least to have known them, probably owned some, or – like me – still own them all. I don’t give books up easily and I never have! These were snapped with my phone.

BIO: National-bestselling and multi-award-winning author, Catriona McPherson (she/her), was born in Scotland and lived there until immigrating to the US in 2010, where she lives on Patwin ancestral lands.

She writes historical detective stories set in the old country in the 1930s, featuring gently-born lady sleuth, Dandy Gilver. After eight years in the new country, she kicked off the comic Last Ditch Motel series, which takes a wry but affectionate look at California life from the POV of a displaced Scot (where do we get our ideas, eh?). She also writes a strand of contemporary psychological thrillers. The latest of these is A GINGERBREAD HOUSE, which Kirkus called “a disturbing tale of madness and fortitude”.

Catriona is a member of MWA, CWA, Society of Authors, and a proud lifetime member and former national president of Sisters in Crime. www.catrionamcpherson.com

From the Booking Desk:

In case you missed my spoiler-free review of A Gingerbread House, you can find that be following the link on the title.

And here is the official synopsis of the novel:

A Gingerbread House

978-0-7278-5001-0

Meet Ivy Stone. A fifty-four-year-old book-keeper from Aberdeen with a second chance at life now that’s Mother’s gone. She’s determined to overcome her shyness and finally make a friend. Meet Martine MacAllister. A grant-writer from Lockerbie, facing her thirties like she’s faced her whole life – working hard and ignoring the racists. If only she wasn’t quite so alone. Join a club, they say. So she has and she’s hoping. Meet Laura Wade. An entrepreneur from Ayrshire, hitting forty and far from ready for it. She’s got her life mapped out and the prospect of it dazzles her. All she needs is to meet the right man. And soon. Luckily there’s no shortage of help for that these days.

The world is full of women and girls searching for something and ready to follow a trail of breadcrumbs to find it.

Enter Tash Dodd. She’s a worker-bee, a grafter, no way a hero. But, when her unremarkable life explodes and her normal family is revealed for what they truly are, her only choice is to embark on a quest for justice and redemption; a quest that soon becomes a race against time.

In this modern fairytale, set in Scotland’s post-industrial central belt, the secrets inside respectable-looking lives curdle, the poison spreads, and the clock is ticking for all the innocents trapped in the gingerbread house.