From the Booking Desk:

The one-and-only Catriona McPherson has been visiting BOLO Books with Guest Posts for each of her new releases almost since the beginning days of this blog–almost 12 years ago. We can always count on her to put a smile on our faces, to reveal some little known Scottish facts, and/or to intrigue us enough to rush out to buy her latest novel. This time the topic is trash…well, sort of. And the title of the new book is Deep Beneath Us (and it’s available now.)

The Plot-Producing Magic of Tidying Up

by Catriona McPherson

When I first started thinking about the story that turned into Deep Beneath Us, I knew I wanted to write three men, good friends although mismatched in age and temperament, who spent their free time together up in the hills around Hiskith Water, in a more than usually isolated bit of south-west Scotland. They could have been hunters, but hunting is for poshos in the UK and these three – Barrett, Gordo and Davey – are anything but posh. They could have been poachers, but I wanted them out on the hills during the day rather than at night. They could have been fishermen, but I hate doing research on topics that don’t interest me and fishing surely doesn’t interest me. Of course, they could have been hillwalkers, but that was a bit wholesome and normal.

Then I got it! And couldn’t believe it had taken me so long. They’re litter pickers. They love the wild hills and the dark loch but they hate the detritus that humans leave behind there. So, the Musketeers were born. Here’s Barrett, musing about their hobby, and doing a bit of that pathetic fallacy stuff too towards the end of the excerpt (because, you know, he’s not just talking about litter any more. Hey, no one said I had to be subtle.)

“He doesn’t need a dog for the hills. His litter-picker gives him purpose. Sometimes, if no one’s watching, the Musketeers hold their pickers high in the air and clack the claws like the legs of giant crickets, like the beaks of metal birds, snick-snick-snick, then they lower them to the ground to peck at crisp packets and chocolate wrappers, orange peel and apple cores, bread bags and pack rings, bottles and bottle necks and bottle shards and splinters, fag ends the colour of bracken, nearly invisible, Rizla packets a bright, fake green like nothing in nature, can after can after can, stark and new and still rolling in a high wind, or flattened and split with sharp edges digging into the ground.

There must be years’ worth underground now, from before the Musketeers began. They could truffle out some of it. They’d need metal detectors to get the rest. But what’s invisible is doing no harm. What does it matter if foreign objects lie under the grass and moss, under the mulch of old stalks, under the leaves rotting where they’ve blown, under the logs mouldering where they fell at the boggy edge of the plantings? What does it matter what’s fallen in the loch and sunk, filling with mud and weed? He’s not – none of them are – the sort to go poking.”

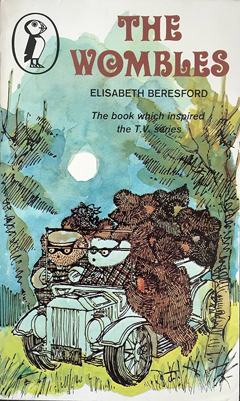

I loved writing the litter! But then I’ve always loved a bit of trash, garbage, rubbish, sheugh . . . call it what you will. It started, I suppose with The Wombles, creatures who live in burrows, collect litter and use it to furnish and decorate their homes.

Like every other British kid, I believed Wombles were real. They looked no more outlandish than badgers and hedgehogs and we’d been exposed to Beatrix Potter and Watership Down, remember. Then, when I found out they were fictional, I thought the place they lived – Wimbledon – was also imaginary. Imagine the confusion when live-action characters seemed to play tennis there.

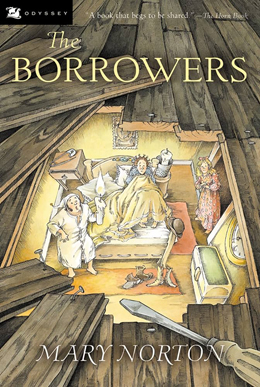

As I grew up, even better and more beloved than Uncle Bulgaria, Tobermory and Co. were The Borrowers.

Now, the Borrowers aren’t immediately all that different from the Wombles: they live out of sight and borrow from “human beans” to furnish and decorate their homes. But! Their homes are our homes. They are tiny people who exist unnoticed in the walls and under the floors, responsible for missing spectacle cases and buttons. If Mary Norton had written the novel today, Pod, Homily and Arrietty Clock would be stealing borrowing charger cables and car keys.

And then at school we all had to read the modern classic Stig of the Dump.

Stig was the imaginary friend to end all imaginary friends. Or was he? The other possibility is that a Neanderthal boy really did live at the rubbish dump near Barney’s house. Did Barney really help him transform his den of rubbish into an upcycled haven, using the dump’s treasures (in the same way that Doris Day transformed the cabin for Katie and Calam, because two wee boys can accomplish just as much as a woman and a whiskbroom, you know)?

The other reason I loved Stig of the Dump, besides the junk, was that it was the first time I’d read a book where you were supposed not to know. I still remember the process of feeling puzzled, then cheated, then honoured. Honoured because the author stepped aside and let his young readers decided for themselves. I still love those kinds of stories today.

And I still love stories set in places full of rubbish.

My favourite thing about Casa Larkin in The Darling Buds of May and its many sequels was always the yard – the army surplus, the loads of olives (in barrels, with Cyrillic writing on), the scrap metal and old timber and decommissioned chamber pots. I don’t have the temperament to be a junk dealer – along with many other Brits, I can’t haggle for toffee – but I love reading about Pop Larkin’s wheeling and dealing, and I do love a junkyard. (I’m writing one now, in the next standalone after Deep Beneath Us. )

In real life I don’t pick up litter in any organised way, although the idea of Planet Patrol, where volunteers go out on paddleboards to remove fishing line, hooks, wrappers, containers and nurdles from lakes and waterways is a very appealing one.

I do finish my morning exercise most days with a handful of drinks cans, burger bags and sweetie packets, always cursing the morons who drop them in pretty places (or ugly places, actually) and occasionally wondering what kind of evening leads to someone throwing a knitting needle out of their car or, one shoe, or – last week – a small saucepan. Human Beans are just as strange as Borrowers, aren’t they?

Usually my morning haul goes in the nearest bin, but litter picking on a beach can sometimes result in a collection worth saving. Here’s what I picked out of the hide-tide seaweed on Vero Beach in Florida a few years ago:

I brought it home and put it on the Cupboard of Much Mess in my hallway. We call him Playboy Turtle, him with his speedboat and his giant flag from Publix’s produce section. I make a very disappointing tourist for owners of souvenir shops, but I’d have made a great Womble.

Serial awards-botherer, Catriona McPherson (she/her) was born in Scotland and immigrated to the US in 2010. She writes: preposterous 1930s private-detective stories including September 2024’s THE WITCHING HOUR; realistic 1940s amateur-sleuth stories, starting the series with IN PLACE OF FEAR; and contemporary psychological standalones, with DEEP BENEATH US coming in June. These are all set in Scotland with a lot of Scottish weather. She also writes modern comedies about the Last Ditch Motel in a “fictional” college town in Northern California, most recently HOP SCOT. Currently, Catriona is at work on the follow-up to IN PLACE OF FEAR, the working title of which is NEXT TO GODLINESS. She is a proud lifetime member and former national president of Sisters in Crime. www.catrionamcpherson.com

Serial awards-botherer, Catriona McPherson (she/her) was born in Scotland and immigrated to the US in 2010. She writes: preposterous 1930s private-detective stories including September 2024’s THE WITCHING HOUR; realistic 1940s amateur-sleuth stories, starting the series with IN PLACE OF FEAR; and contemporary psychological standalones, with DEEP BENEATH US coming in June. These are all set in Scotland with a lot of Scottish weather. She also writes modern comedies about the Last Ditch Motel in a “fictional” college town in Northern California, most recently HOP SCOT. Currently, Catriona is at work on the follow-up to IN PLACE OF FEAR, the working title of which is NEXT TO GODLINESS. She is a proud lifetime member and former national president of Sisters in Crime. www.catrionamcpherson.com